Tumours or cancer of the brain

The incidence of brain tumours in dogs and cats is unfortunately the same as in people.

A brain tumour can be devastating to an animal and most cannot be cured. Currently, the only option for treatment is to help the animal have as good a quality of life as is feasible for as long as possible. Unfortunately all brain tumours end up being fatal diseases.

What is a brain tumour?

Tumours (or cancers) are growths of abnormal cells in the body. Brain tumours can be classified into three types:

The primary form of brain tumour occurs when brain tissue grows uncontrollably. There are several types of primary brain tumours, including those formed in the lining of the brain’s surface (meningiomas), the lining of the ventricle (ependymomas), the choroid plexus (choroid plexus tumours), and the brain parenchyma itself (gliomas).

Secondary brain tumours: Tumours can grow from tissue surrounding the brain, either pressing on or infiltrating the brain such as nasal or ear tumours and tumours of the skull.

Metastatic brain tumours: These arise when fragments of tumours elsewhere in the body break off and travel through the bloodstream to the brain, where they settle and begin to grow.

Generally, when an animal has a brain tumour, its signs are caused by the tumour growing and exerting pressure on normal brain tissue. This causes brain damage and inflammation.

What causes a brain tumour?

Cancer is the result of a genetic mutation, which causes uncontrolled division of cells, resulting in an expanding mass. Most animals with brain tumours are over 5 years of age (median 9.5 years at diagnosis in dogs, over 11 years in cats).

In the case of primary brain tumours, there is a layer of cells in the brain that have the capacity to continue to divide. Sometimes cancers can form in this region.

What are the signs of a brain tumour?

Different parts of the brain can exhibit different clinical signs as a result of brain tumours. Seizures (fits) are often the first sign of the disease. It is common for dogs experiencing seizures to collapse, salivate profusely, thrash around, and sometimes void their bowels or bladders. Seizures like these are likely to be permanent. Dogs may also exhibit blindness, personality changes, profound lethargy, and circling. There are times when people notice that their dog has a headache. Whatever treatment course you choose, some of these signs may be permanent.

How do I diagnose a brain tumour?

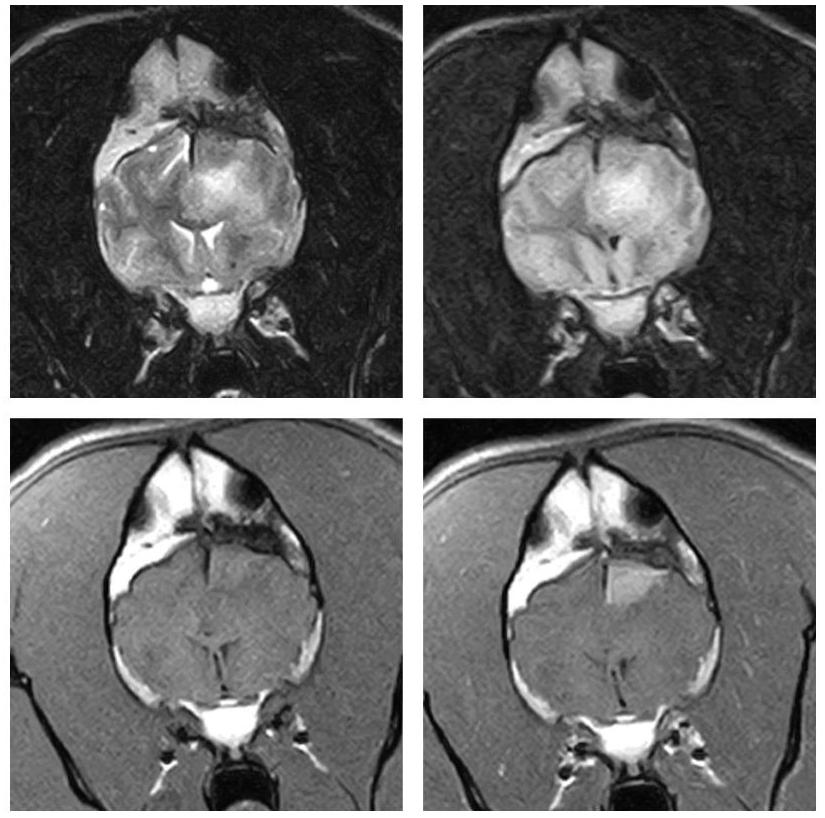

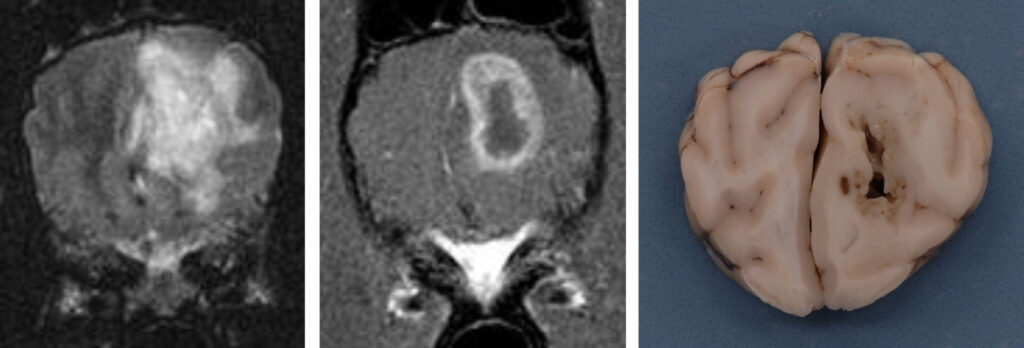

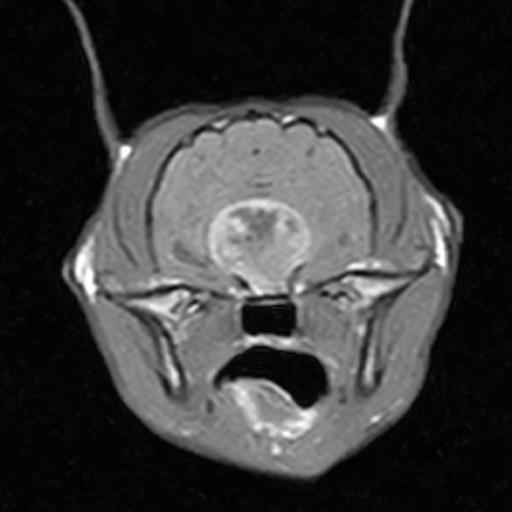

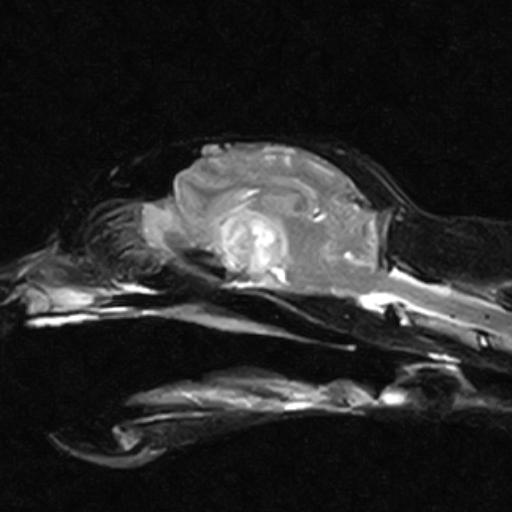

In order to diagnose brain tumours, CT-scans or MRI-scans are used to image the brain. Despite the fact that these tests are very good at detecting the presence of a mass in the brain, they are very poor at identifying its exact nature (i.e. whether it is a tumour, inflammation, or bleeding within the brain).

When it comes to people, a biopsy of a brain tumour is the preferred way to determine the type of tumour and other information regarding treatment and prognosis. Normally, we do not recommend brain biopsy in animals since it is a very invasive and potentially risky procedure. A veterinary neurologist will often diagnose a tumour type based on key features on scans. This approach has limitations, so it is difficult to provide accurate information regarding treatment and prognosis.

Through x-rays, ultrasound scans or CT scans, it may be necessary to rule out cancers elsewhere in the body, or the possibility of metastatic brain tumours.

Can brain tumours be treated?

Animals can now be treated for brain tumours thanks to advances in veterinary care, although the majority of them cannot be cured. A pet’s treatment is usually aimed at providing the best quality of life possible for as long as possible. Regardless of what treatment is chosen, if a dog is having seizures, they should receive medication to control them. Seizures are likely to worsen if not treated.

How can brain tumours be treated?

Treatment and prognosis for brain tumours vary according to their type. It depends on whether the tumour is primary, secondary, or metastatic. Generally speaking, treatment of tumours can be palliative or definitive.

Generally, palliative treatment involves:

• Controlling signs e.g. anti-epileptic medications to prevent seizures

• Using steroids to reduce swelling and pressure on the brain, as well as prevent fluid from developing around a tumour

The definitive treatment generally consists of three options:

• Surgery: Surgically removing the tumour completely is the ultimate goal of cancer surgery. It is rare for this to be possible with brain tumours, and nearly always tumour cells are left behind, causing them to grow back. By removing the bulk of the tumour, other treatments may have a better chance of success; the remaining cells may become more ‘sensitive’ to radiation after removal of the bulk of the tumour during surgery. Most brain tumours in humans are treated with polytherapy (a combination of medication, surgery, and radiation). As a result of surgery, it may be possible to obtain a sample of the mass and identify its nature. This will allow a more accurate prediction of the patient’s future. It is not possible to remove all brain tumours in dogs and cats surgically; surgical feasibility depends on where in the brain the tumour is located. On the surface of the brain, tumours are more likely to be removal via surgery. A surgeon would have to cut through a large area of healthy brain tissue in order to reach a tumour deep within the brain. This could have disastrous consequences for the patient’s recovery. There are several options for treatment, but surgery is the most invasive and costly. Brain surgery can sometimes result in irreversible damage to the brain, although many dogs recover well without complications. It has been reported that some owners have noticed a change in their pet’s personality and behaviour following surgery. Surgery on the brain involves risks, especially if the patient has other health issues, since it requires a lengthy anaesthetic. There are times when a patient may not recover from surgery. Choosing this option may provide a pet with the longest period of quality of life although the associated risks must be considered. With few exceptions, veterinary neurologists do not recommend surgery for deep-seated brain tumours because it can cause more harm than benefit. Meningiomas or some tumours of the pituitary gland can, however, be surgically treated, often with good results.

• Radiation treatment (radiotherapy) is sometimes used to slow down or shrink these tumours. A drastic and rapid improvement in signs can be achieved through radiation therapy. When pets are not severely affected, the benefits of this treatment far outweigh the risks. Occasionally, animals may experience side effects from radiation treatment, such as nausea, mouth ulcers, ear infections, or, rarely, blindness. Medications can control most of the side effects of radiation. Radiation treatment, in conjunction with medication, can enhance quality of life for a longer period of time than medication alone. It is unfortunate that radiation rarely completely destroys tumours, and recurrences are common after eight to fourteen months of remission. In the United Kingdom, radiotherapy is also considered a very specialist treatment and only a few centres provide this service. As a result, radiation seldom completely destroys a tumour, and remissions last between 8 and 14 months before a tumour recurs.

• Chemotherapy to limit growth/spread of the tumour. The most common chemotherapy drugs for glioma are lomustine (CCNU) and temozolomide. Animals generally tolerate lomustine well. It crosses the blood-brain barrier easily and targets brain tumours. We administer lomustine once every six weeks using an oral dose. This has the disadvantage of being impossible to withdraw once given. Also very well tolerated, temozolomide is given by mouth. There is the possibility of stomach upsets (vomiting), diarrhoea, suppression of the bone marrow (which could lead to anaemia and lower white blood cell counts) as well as liver and kidney problems as a result of long-term use. The treatment may require occasional visits to the practice. Every few months, blood tests are recommended to assess the function of organs that may be affected. How often this is required will be dependent on the pet’s response to treatment.

Treatment options for the pet are determined by the suspected tumour type, the owner’s wishes, and a discussion with your veterinary neurologist. Chemotherapy is not used at high doses in veterinary medicine, since the goal is to limit the growth of a tumour, not to destroy it. As a result, dogs and cats usually tolerate chemotherapy well and side effects are extremely rare.

Sometimes steroids are called chemotherapy, but they are more commonly known as anti-inflammatory medications, which are highly beneficial in reducing the signs of tumours in the short term. There are often side effects associated with steroid use. Steroids can cause increased thirst and appetite (resulting in urination and weight gain), lethargy, panting, and an increased likelihood of infection (respiratory, urinary).

What is the prognosis?

Pets with brain tumours are treated to prolong their life and to ensure a good quality of life. Trying to predict how long an animal will live with a brain tumour can be very difficult because so many factors play into this estimation, including the type of tumour (which determines how quickly it grows), its size, location, and treatment. Despite the fact that many animals only live a few months after being diagnosed with a brain tumour, with the right care they can live a good quality of life. The average remission time ranges from 1 to 6 months with corticosteroids alone, 8 to 14 months with radiotherapy alone, and 12 to 20 months with surgery and radiotherapy combined.