Background and Cause

Patellar luxation is a common orthopaedic issue in dogs, and refers to the dislocation of the patella from its groove (the trochlea) at the front of the knee joint. It is less common in cats, but does occur. In both dogs and cats, some breeds are predisposed.

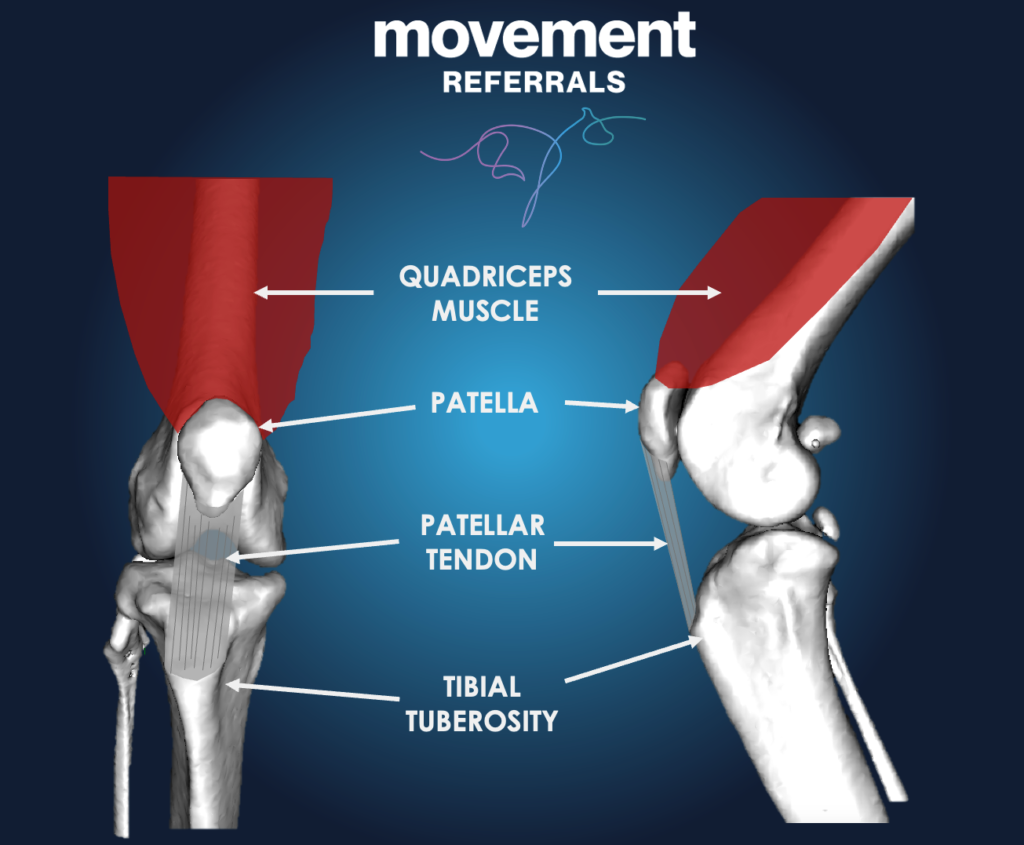

It is helpful to understand the anatomy of the “quadriceps mechanism”, which is made up of:

- The quadriceps muscle group (which originates around the hip and runs down the front of the thigh), and inserts on the patella.

- The patella (the “kneecap”) is a bone that sits in the tendon of the quadriceps muscle.

- The patella tendon, which is a large, flat tendon that links the patella to the tibial tuberosity.

- The tibial tuberosity is the pointy prominence at the front of the tibia, just below the knee.

When the quadriceps contracts, the patella is pulled upwards and the knee straightens. When the knee bends and the quadriceps relaxes, the patella is pulled downwards.

This means that, when an animal is in motion, the patella is constantly running up and down on the front of the femur.

To stabilise the patella, and to keep it running in line with the motion of the knee, it sits within a groove on the front of the femur, called the trochlear groove. On either side of the patella, forming the groove, is a trochlea ridge.

The trochlea groove and the back of the patella, where they contact each other, are covered in articular cartilage, and the joint is bathed with joint fluid. Cartilage running on cartilage, bathed in joint fluid, creates very little friction: the bones glide against each other, and the joint functions in a stable and efficient manner.

In cases of patellar luxation, there is generally a malalignment, so that the quadriceps mechanism does not line up with the trochlear groove, and the patella has a tendency to slip out of the groove, and over one of the ridges. In addition, the groove might be poorly formed, or one of the trochlear ridges might be worn down, so the stabilising effect of the groove is lost. Also, the soft tissues on either side of the patella might stretch and loosen, and on the other side they might become contracted and tight.

We grade patellar luxation based on how much time the patella spends outside the groove, and how easy it is to manipulate it back into place. The grade of luxation is just one of the criteria that we use to make decisions about treatment. Other factors include the size of the dog, the clinical impact the luxation is having, and whether we think there is erosion of the cartilage.

Clinical Signs

Some dogs with very mild patella luxation have no clinical signs at all, and it is only detected by a vet during a routine clinical examination. These cases rarely require treatment. An important exception might be a medium or large breed dog that is diagnosed when they are a puppy, as they are at risk of rapid progression of cartilage erosion and there can be an argument for early intervention.

The “classic” presentation of patellar luxation is skipping: dogs or cats might walk normally most of the time, and intermittently hold up one of their back legs (or alternate which back leg they carry, as patellar luxation often effects both). Some pets might have more persistent lameness, or stiffness after rest.

In some animals, the onset of patellar luxation can be sudden, and might be associated with an episode of obvious pain and severe lameness.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can often be made on the basis of clinical examination by an experienced veterinary professional. The patella can usually be manipulated in to and out of the trochlear groove. Most commonly, the patella luxates medially (towards the inner side of the leg), but it is important to always check for lateral luxation (towards the outside of the leg).

It is also important to assess patients for other orthopaedic conditions that might affect treatment and/ or outlook: CCL failure is often diagnosed alongside MPL in adult dogs, and hip dysplasia is seen concomitantly in some cat breeds, as examples.

Radiography (x-rays), and especially CT examination, can be very useful in accurately assessing skeletal conformation, as some pets might need more complicated corrections.

Treatment

Some dogs and cats, with low-grade patellar luxation and no, or very mild, clinical signs, might be amenable to non-surgical management.

The vast majority of dogs and cats with patellar luxation can be successfully managed with “routine” surgical procedures, which generally comprise some combination of:

- Tibial Tuberosity Transposition (TTT). The tibial tuberosity is the lower attachment of the quadriceps mechanism. In dogs, it is prominent and can be detached from the tibia, moved sideways to better align the patella with the trochlear groove, and be fixed in place with implants. It will eventually heal in its new position. This procedure can also be performed in cats.

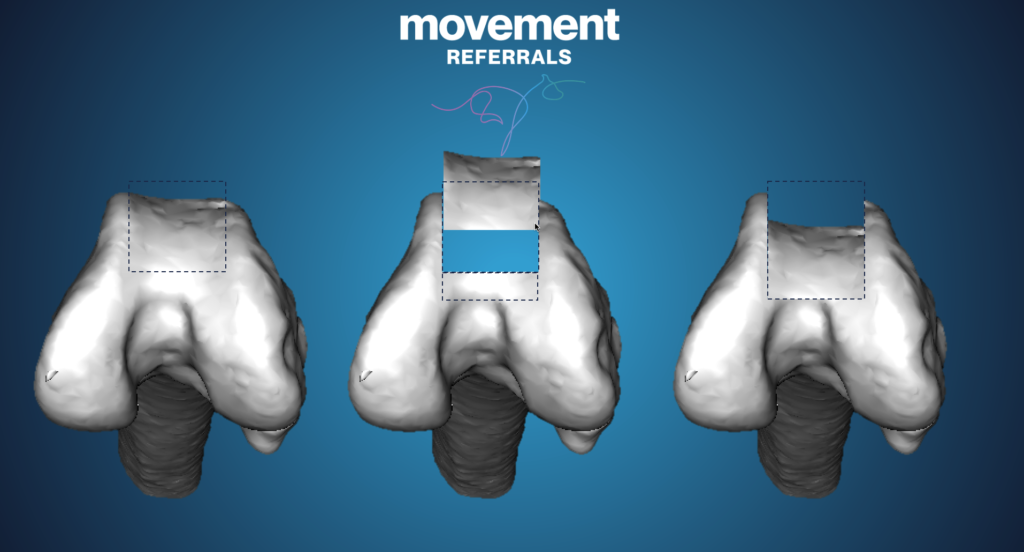

- Trochleoplasty. This procedure aims to deepen the groove and provide more prominent ridges that stabilise the patella. A wedge or a block of bone that preserves the articular cartilage is cut free from the middle of the groove. A deeper fragment of bone is then removed, and the original fragment replaced in the defect. This deepens the groove, whilst maintaining the important cartilage.

- Imbrication.The joint capsule and ligaments on one side of the patella is often stretched and loose. These tissues can be tightened (imbricated) to “pull” the patella back towards the groove.

- Soft-tissue release. The joint capsule and ligaments on the other side of the patella can become tightened and contracted. In order to allow the patella to return to its normal position in the groove, these tissues might need to be “released” through cutting or stretching.

A small minority of pets might have more complex abnormalities of their skeleton, and require correction of angular (bends) or torsional (twists) deformities of the femur and/ or tibia. Some animals might have extensive degenerative changes in the trochlear groove, and these patients might benefit from partial joint replacement (patellar groove replacement, PGR).

Outcomes

We expect a high rate of success when treating patellar luxation in dogs and cats. Although it is a common condition, there are many variables to consider when making clinical decisions, including during the surgery. Surgeon experience helps to minimise the risk of complications and maximise the chances of a successful outcome.

and ensuring their furry companions lead active and comfortable lives.