Introduction

Failure of the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) is the most common orthopaedic condition in dogs. It causes pain, lameness, and stiffness, and can lead to the development of other joint injuries such as tearing of the medial meniscus, and degenerative joint disease (osteoarthritis, OA). Clinical outcomes following surgery are generally considered to be excellent, with most dogs returning to good levels of activity.

Background

The CCL is one of four major ligaments that stabilise the knee (in dogs, we call this joint the stifle). There are two collateral ligaments that run down each side of the joint, and two cruciate ligaments that sit inside the joint, and cross over each other. The caudal cruciate ligament is rarely injured, but failure of the cranial cruciate ligament (known as the anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, in people) is one of the most common orthopaedic conditions in dogs. The CCL is illustrated in picture 1.

The CCL/ ACL has several jobs:

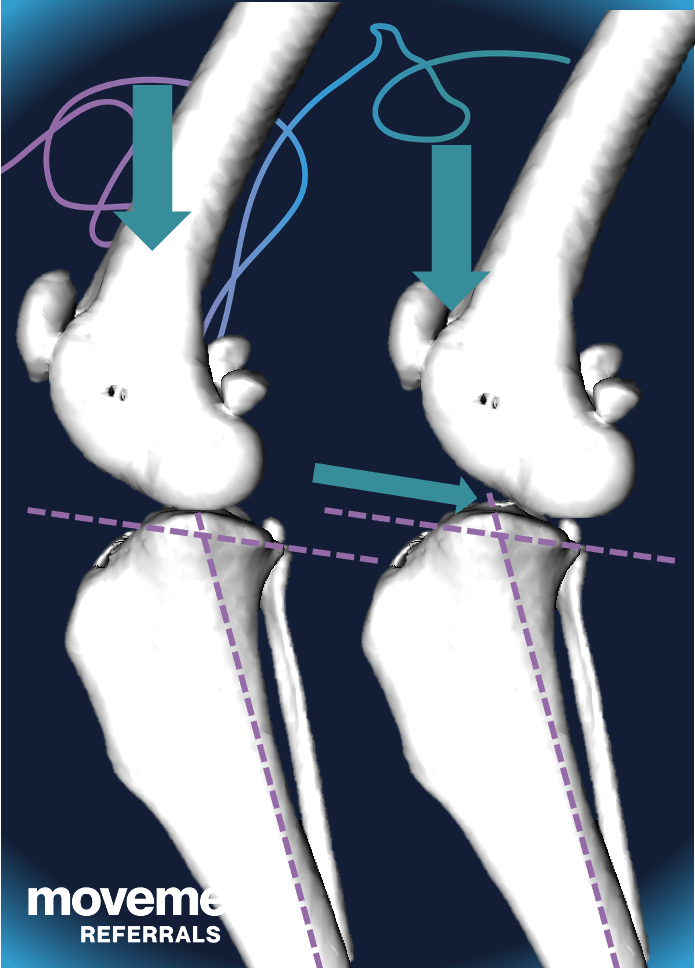

- It prevents the tibia (shin bone) from sliding forwards relative to the femur (thigh bone). You could also say that it prevents the femur from sliding backwards relative to the tibia.

- It prevents the tibia from rotating or twisting inwards relative to the tibia.

- It prevents the stifle/ knee from hyperextending (bending backwards).

In dogs, the top of the tibia slopes downwards from front to back. This slope is called the tibial plateau angle. This slope is usually between 25˚ and 30˚ in dogs. This means that there is a tendency for the femur to slide backwards in a dog’s stifle when the CCL has failed. This slope is one of the reasons that canine CCL failure is treated differently than ACL injury in people.

CCL failure is generally considered to be a degenerative condition in dogs (it is sometimes called cruciate “disease”), and is only rarely associated with a traumatic “injury”. This is another reason why the treatment and expectations for CCL failure in dogs differs from those for human ACL injury.

Does your dog have CCL failure?

If your dog is limping, or has stiffness after rest, in a hind limb, then there is a good chance they have CCL failure or disease.

Some dogs with CCL failure will suddenly become very lame whilst exercising, and might even yelp or cry at first. Even though the onset of lameness is very sudden, the ligament might have been degenerating for a while.

In other dogs, the onset of lameness (limping) is more gradual, and the severity might vary. It is generally worse after rest, when the joint has “stiffened up”, and is usually exacerbated by longer and more boisterous exercise periods. The lameness might resolve completely when they are rested for a few days, only to recur as soon as anything like “normal” activity is resumed.

Occasionally, a dog might suffer CCL failure in both hind limbs at the same time. If the pain is severe, this can look like the dog is very weak in the back end and mimic a spinal problem. If the signs come on slowly and are less severe, it can look like a generally stiff gait, mild weakness, or even just reduced activity levels and an unwillingness to walk.

How is CCL failure diagnosed?

When the CCL is completely ruptured, instability can usually be detected by a vet using either the cranial draw test or the tibial compression test. These tests are demonstrated HERE. This can often be done with the dog fully conscious. If the dog is painful or tense, they might have to be sedated.

If the CCL is only partially ruptured, those tests might be negative. It is important to perform the tests several times, each time with the stifle at a different angle. This helps to detect CCL failure when only some of the fibres are ruptured. Sometimes, the stifle is completely stable when only a few fibres are ruptured, but it is still inflamed and painful. In these dogs, CCL failure might be suspected if there is pain in the joint, usually when it is extended.

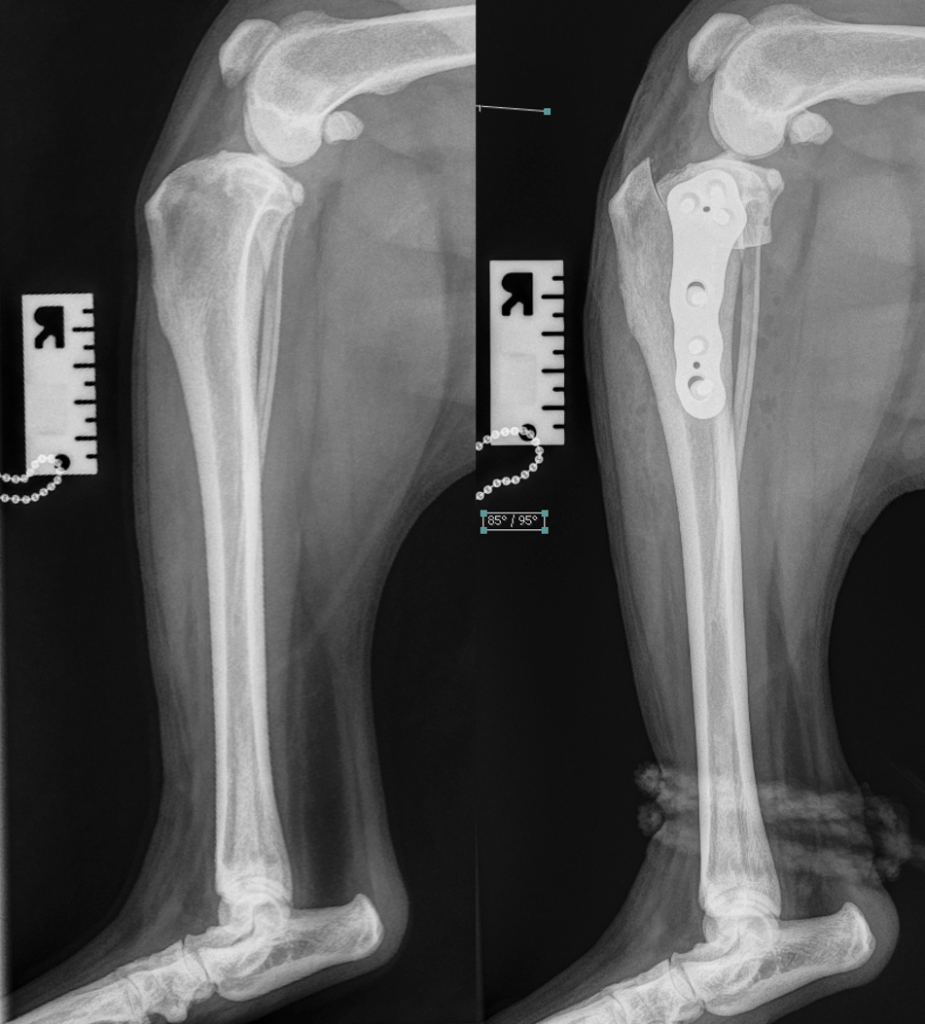

X-ray images (radiographs) can be useful in the diagnosis of CCL failure. An increased volume of joint fluid (called an effusion) can be seen on radiographs, and, if the problem has been present for a few weeks or more, there might be signs of osteoarthritis. Radiographs are also useful in ruling out other causes of stifle joint pain and lameness.

Pain in the stifle and the radiographic changes are not specific to CCL failure. Therefore, uncommonly, partial CCL failure might only be completely confirmed by surgical exploration. Arthroscopy is highly valuable in this situation, as it gives an excellent view of the joint in a minimally invasive fashion.

CCL failure is sometimes diagnosed on a CT scan, usually when the scan has been performed to image multiple areas. MRI is very rarely used to diagnose CCL failure in dogs for cost and logistical reasons.

How is CCL failure treated in dogs?

The majority of dogs will benefit from surgical management when their CCL fails. Joint instability is a source of pain and is a major driver of joint degeneration (osteoarthritis), and surgery helps to stabilise the joint.

Non-surgical management includes body weight management, exercise moderation, pain-relief and other strategies including forms of physiotherapy. Clinical signs such as pain and lameness tend to improve when the dog is rested, and frequently recur when normal exercise is resumed.

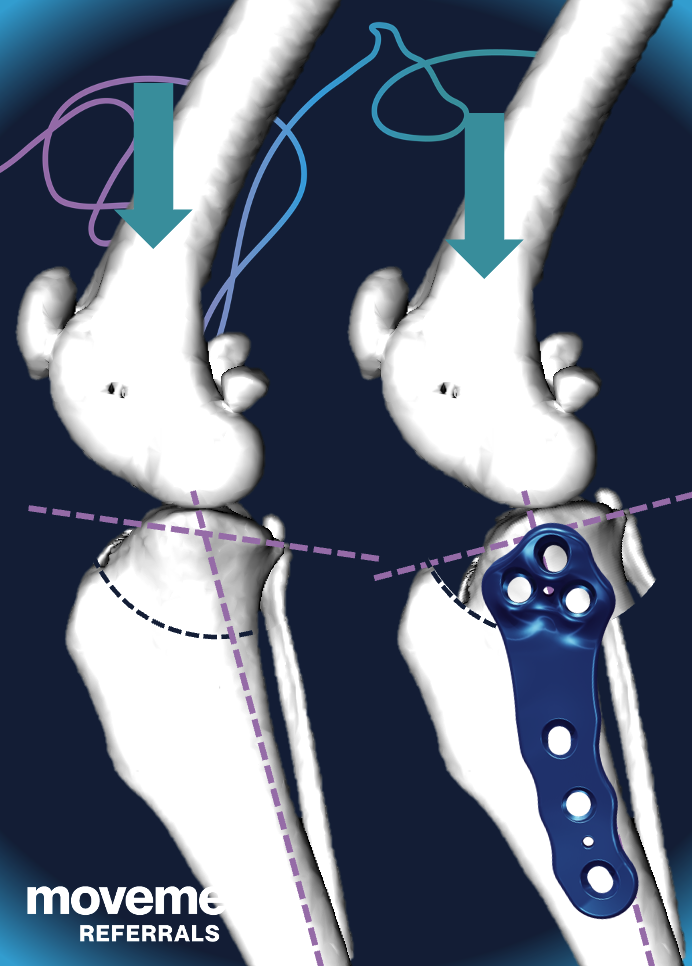

Based on the best evidence that is currently available, it is very likely that the most effective surgical treatment for CCL failure is the tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO). In this procedure, the backward slope at the top of the tibia is “levelled” so that the natural tendency for the femur to slide down that slope is neutralised. More surgeons recommend this technique than any other, and there is good quality evidence that it is more effective than some other popular surgical options. You can watch a video that explains how TPLO is performed and helps to stabilise the stifle joint HERE.

Another popular surgical technique for CCL failure in dogs is lateral suture (also known as lateral fabellotibial suture, or extracapsular stabilisation). This procedure can be useful in cases in where TPLO is not possible, or occasionally as an adjunct to TPLO. However, there is good evidence that it is not as effective as TPLO in restoring normal function in large dogs, and this might also be true for small dogs.

Other surgical techniques are less commonly used for the treatment of CCL failure, but, based on current evidence, most of these are either obsolete (because they have been proven to be less effective) or are novel and unproven.

What is the expected outcome?

The vast majority of dogs that are treated surgically for CCL failure have an excellent outcome: over 90% of owners of Labradors, for example, that have TPLO score their satisfaction level as 9/10 or 10/10 (compared with 75% of owners whose Labradors have lateral suture surgery). The first stage of recovery is mostly about allowing the osteotomy to heal. This typically takes between six and twelve weeks. Activity should be carefully controlled for this period, though lead walking is allowed. The second stage of “recovery” is to recover from the CCL failure. Although dogs are allowed to return to unrestricted activity after a few weeks, some evidence suggests that limb function can continue to improve