Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis in dogs and cats. In dogs, osteoarthritis is nearly always secondary to some other primary disorder of a joint such as dysplasia, instability, or joint injury such as a fracture. As such, it is often important to find out what the primary cause of the osteoarthritis is and this might involve clinical examination, diagnostic imaging (X-rays, CT scan, MRI scan) or arthroscopy (key-hole surgery).

Osteoarthritis affects all aspects of a synovial joint. Joints surfaces are lined with a very thin tissue called articular cartilage and this is gradually eroded during the process of osteoarthritis. The joint is surrounded by a soft tissue capsule which is lined by a reactive tissue called synovium. The synovium becomes inflamed during osteoarthritis and most of the pain in osteoarthritis in fact comes from the synovium. The bones either side of the joint also change in osteoarthritis: the bone beneath the cartilage can becomes sclerotic (hard and dense) and new bony growths (osteophytes) can appear at the margins of the joint. When cartilage becomes fully eroded, the bone underneath can become exposed and this can cause more severe pain.

Assessing the severity of osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a disorder that affects mobility and, as such, assessing a dog or cat’s mobility is the most important aspect. This can be done through a combination of input from the pet owner, alongside professional assessment of gait and a physical examination. For pet owner input, we strongly recommend the use of a validated client-reported outcomes measure (CROM) such as the ‘Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs’ (LOAD) instrument. LOAD is recommended by the World Small Animal Veterinary Association for the assessment of chronic pain in dogs (WSAVA Pain Guidelines 2022). LOAD was developed by Movement Referrals’ very own, Professor John Innes, when he worked at University of Liverpool. LOAD has been through extensive validation and has been translated in to 15 or more languages. You can read more about LOAD here.

Sometimes, the osteoarthritis has advanced to the point where it is the main cause of pain from a joint. In such circumstances, there are different ways to manage the problem:

Conservative management

Conservative management involves a combination of measures designed to reduce pain and improve mobility. Things to consider include:

Optimising bodyweight and avoiding overweight and obesity

Using controlled exercise programmes, and possibly hydrotherapy and physiotherapy

Environmental adaptations – avoiding slippery floors, using ramps.

Medication – there are various types of medication that can be used for osteoarthritis and careful consideration of the available options is important to weigh up the benefits and possible risks. Medication may be required long-term, and so careful monitoring under veterinary supervision is important.

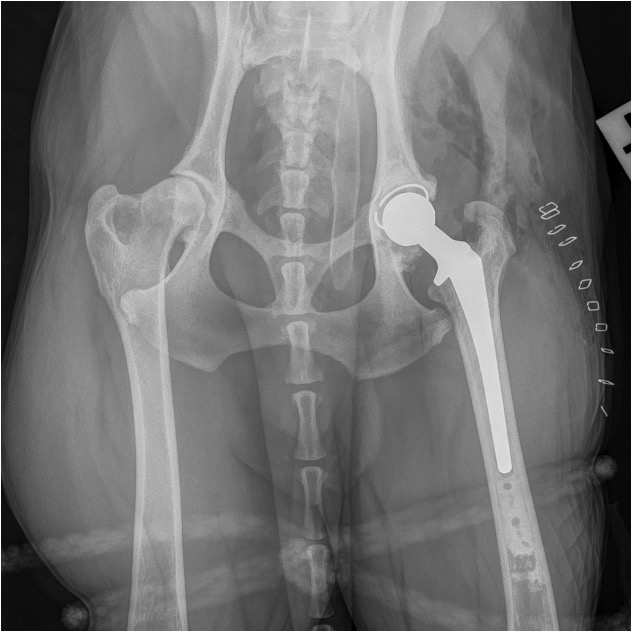

Surgery – when osteoarthritis becomes so severe that medication is not sufficient to maintain quality of life, sometimes surgery is considered. Again, this needs careful consideration and the benefits and risks need to be carefully discussed. Sometimes, in the right circumstances, surgery is performed as an alternative to medical management. Surgery may involve total joint replacement, such a total hip replacement, fusing of the joint (arthrodesis), or removal of part of the joint (excision arthroplasty).

Total hip replacement is a very successful operation and can return a dog to excellent mobility without ongoing pain. However, careful counselling with an experienced surgeon is necessary to weigh up the benefits versus the risks. You can read more about hip replacement on our ‘hip‘ page.

Publications from Movement Vets surgeons

Alves, J. C., and J. F. Innes. 2023. ‘Minimal clinically-important differences for the “LiverpoolOsteoarthritis in Dogs” (LOAD) and the “Canine Orthopedic Index” (COI) in dogs with osteoarthritis’, Plos One, 18.

Cachon, T., O. Frykman, J. F. Innes, B. D. X. Lascelles, M. Okumura, P. Sousa, F. Staffieri, P. V. Steagall, B. Van Ryssen, and Coast Dev Grp. 2018. ‘Face validity of a proposed tool for staging canine osteoarthritis: Canine OsteoArthritis Staging Tool (COAST)’, Veterinary Journal, 235: 1-8.

Garvican, E. R., A. Vaughan-Thomas, P. D. Clegg, and J. F. Innes. 2010. ‘Biomarkers of cartilage turnover. Part 2: Non-collagenous markers’, Veterinary Journal, 185: 43-49.

Garvican, E. R., A. Vaughan-Thomas, J. F. Innes, and P. D. Clegg. 2010. ‘Biomarkers of cartilage turnover. Part 1: Markers of collagen degradation and synthesis’, Veterinary Journal, 185: 36-42.

Girling, S. L., S. C. Bell, R. G. Whitelock, R. M. Rayward, D. G. Thomson, S. C. Carter, A. Vaughan-Thomas, and J. F. Innes. 2006. ‘Use of biochemical markers of osteoarthritis to investigate the potential disease-modifying effect of tibial plateau levelling osteotomy’, Journal of Small Animal Practice, 47: 708-14.

Innes, J. F., J. Clayton, and B. D. X. Lascelles. 2010. ‘Review of the safety and efficacy of long-term NSAID use in the treatment of canine osteoarthritis’, Veterinary Record, 166: 226-30.

Innes, J. F., M. Sharif, and A. R. S. Barr. 1998. ‘Relations between biochemical markers of osteoarthritis and other disease parameters in a population of dogs with naturally acquired osteoarthritis of the genual joint’, American journal of veterinary research, 59: 1530-36.

Lascelles, B. D. X., D. Knazovicky, B. Case, M. Freire, J. F. Innes, A. C. Drew, and D. P. Gearing. 2015. ‘A canine-specific anti-nerve growth factor antibody alleviates pain and improves mobility and function in dogs with degenerative joint disease-associated pain’, Bmc Veterinary Research, 11.

Walton, M. B., E. Cowderoy, D. Lascelles, and J. F. Innes. 2013. ‘Evaluation of Construct and Criterion Validity for the ‘Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs’ (LOAD) Clinical Metrology Instrument and Comparison to Two Other Instruments’, Plos One, 8.