Degenerative Lumbosacral stenosis

In dogs, lumbosacral stenosis (a compression of the spine in the lower back) can affect large, middle-aged breeds (particularly German shepherds). Different abnormalities can result in the compression of the lumbosacral area of the spinal column, including misalignments, malformations, bony changes, and arthritis.

What is degenerative lumbosacral stenosis?

A disc of cartilage cushions the vertebrae (bones of the spine) of dogs. It is possible for these discs to rupture (herniate) into the vertebral canal, causing compression of the spinal cord. In general, this condition is referred to as intervertebral disc disease, and it can affect any area of the spine, from the neck to the tail. This condition can cause degenerative lumbosacral stenosis (DDLSS) when it occurs along the lumbosacral area of the spine. In the lower back, the lumbosacral area is where the last few lumbar vertebrae (L5, L6, and L7) connect with one another, and where L7 (the last lumbar vertebra) connects with the sacrum. This is where nerves originate that supply the rear legs and tail, as well as controlling the bladder and bowel.

Stenosis refers to a narrowing of a space. DLSS can be caused by misalignment, malformation, bony changes, or arthritic changes that compress the spine and its nerves within the lumbosacral region. While disc herniation can contribute to DLSS, it is not something we always see. In addition, arthritic bone can build up around the nerves that supply the bowel, bladder, and back legs. Signs can include pain, lameness, urination/faecal incontinence, and lameness.

What are the signs of degenerative lumbosacral stenosis?

As DLSS progresses, the signs and signs may vary:

- Mild/moderate to severe lower back pain

- Experiencing pain when extending the rear legs

- Having difficulty standing or walking (especially with the back legs)

- Climbing stairs or jumping with difficulty

- A dog’s rear paws dragging, knuckling, or scuffing

- Having a weakness in the rear legs

- There may be lameness in one or both of the back legs, often most apparent at rest when the dog is not putting full weight on the affected limb

- The tail may hang limp or be held very low as if paralysed when touched or moved

- Urinary and/or faecal incontinence or retention

- Pain-related aggression

Veterinary assistance should be sought immediately if the pet is in pain, having difficulty walking, or having ‘accidents’ around the house (having urination or defecation abnormalities).

What causes degenerative lumbosacral stenosis?

Dogs can be born with DLSS (meaning they can have abnormalities that cause it to develop later in life) or they can acquire it. The congenital disease occurs in dogs between the ages of 3 and 8 years, while the acquired disease occurs in dogs between the ages of 6-7 years.

Congenital DLSS is caused by instability in the area or by malformation of the vertebrae. In the acquired form, the spinal cord and nerves in the lumbosacral area are compressed due to degenerative (usually arthritic) changes. Also, DLSS can be acquired through wear and tear on the intervertebral discs in the area, causing them to degenerate and eventually herniate into the vertebral canal.

How can I diagnose degenerative lumbosacral stenosis?

An x-ray is recommended if the pet displays signs of DLSS. Even though x-rays may show narrowing or arthritic changes in the lumbosacral area, this test result can be normal in some dogs with DLSS. X-rays can assist in ruling out tumours, fractures, and other conditions that can cause clinical signs similar to DLSS. Additionally, dogs that do not exhibit any obvious signs of illness may have dramatic changes in their lumbosacral region when x-rayed.

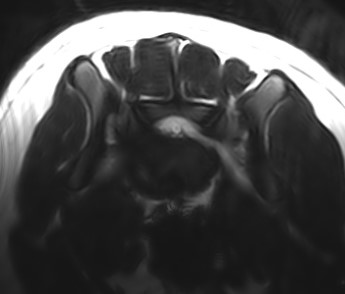

Other diagnostic tests include computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Some veterinary practices do not have CT and MRI equipment, so referral to a specialist is a good idea.

How is degenerative lumbosacral stenosis treated?

The severity of lumbosacral stenosis determines how it is treated. Veterinary conservative management may be recommended if pain is mild to moderate and the dog is still urinating and defecating normally. In general, this involves rest and confinement for several weeks, along with pain and inflammation medications. There may be times when a steroid injection is given to the affected area to see if this improves the dog’s signs.

Surgical intervention may be recommended if the dog improves initially but then relapses. Additionally, surgery may be recommended for dogs with severe pain, unresponsiveness to conservative treatment, or reduced urine and faecal control. Most dogs will be able to return to normal function once the spinal cord compression is relieved through surgery. If significant urinary or faecal incontinence has occurred, the prognosis for full recovery may not be as good.

In terms of surgery, there are many options, and this partly reflects the fact that no surgical treatment is perfect. One approach that seems to be effective is removing the arthritic bone around the affected nerves. This procedure is called a foraminotomy and is often performed on both sides (bilateral foraminotomy). Occasionally, screws and cement may be used to stabilise the lumbosacral region.

Dogs suffering from DLSS must receive adequate at-home nursing care to reduce future complications and maintain their comfort, cleanliness, and quality of life, whether they are being treated with medication and rest/confinement or recovering from back surgery:

- There is no doubt that physiotherapy is an important part of recovery, and it’s very important to find a centre that can guide the owner through this process.

- Prevent pressure sores by providing soft, padded bedding and turning the pet frequently (every few hours).

- Hands-on feeding is recommended, and food and water should be placed near the dog so that it can easily reach them. It may be necessary to assist the pet in lying sternally (on the elbows with the chest on the floor); this position prevents accidental choking while eating or drinking.

- A dog that cannot control urination or bowel movements needs frequent baths and clean bedding. In addition to keeping the pet dry and clean, this can prevent urine scalding and other complications.

- When a dog with DLSS cannot walk, it may still hold its urine for too long, which can cause urinary tract infections, even if it has adequate nerve control. Taking a large or heavy dog outside to eliminate on a regular basis may be helpful, but this can be challenging.

- Infections of the urinary tract and skin wounds (from urine scalding and bed sores) may require antibiotic treatment periodically. Periodic bacterial culture testing of urine may also be recommended to ensure that infections are appropriately treated. To facilitate regular bladder emptying, a urinary catheter may be recommended.

- Pets who cannot walk and who cannot receive at-home nursing care may need to stay in a hospital until their condition improves so that they are able to stay at home when they are better.

If the pet successfully recovers after medical treatment (rest and medication), actions that jolt the spine (e.g. leaping and jumping) should be minimised to help reduce the chance of recurrence.